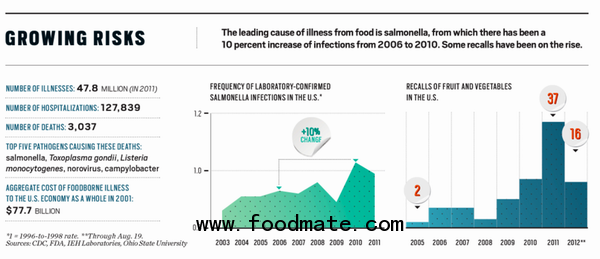

Widely-touted statistics about the prevalence of food poisoning cast some serious aspersions on that idea. In 2011, 48.7 million Americans contracted a foodborne illness. Of those, 127,839 were hospitalized and 3,037 died.

But the blistering cover story of the November 2012 issue of Bloomberg Markets magazine dispels any lingering doubt about the safety of the American food market. And shows just how little the country's food safety system has improved in the past century. It reveals the extent to which the federal government's lack of food safety regulation allows contaminated food to slip through the cracks to be sold in stores, leading to millions of preventable illnesses every year.

The basic problem, as depicted in the story co-written by Stephanie Armour, John Lippert and Michael Smith, is that the FDA, the federal agency assigned to monitor the safety of all food sold in the U.S. save meat, poultry and dairy, does not have the resources to adequately inspect the food Americans eat. As a result, the FDA outsources much of its inspection duties to private agencies, which are often supported by the food industry itself and which are often subject to little (if any) government oversight.

The most damning facet of the Bloomberg Markets story is its exposure of the many instances in which a private food inspection agency certified a producer as safe just weeks before or after food from that producer sickened, and even killed, scores of people. The first page of the story includes the following shocking passage:

Six audits gave sterling marks to the cantaloupe farm, an egg producer, a peanut processor and a ground-turkey plant -- either before or right after they supplied toxic food. Collectively, these growers and processors were responsible for tainted food that sickened 2936 people and killed 43 in 50 states.

Why is the situation so bleak? Much of the time, according to the story, "for-hire auditors have financial ties to executives at companies they're reviewing." Sometimes, the food producers themselves set the standards that the inspectors are instructed to inspect. Much of the time, the inspectors never even test for pathogens. They often don't even "set foot in the production area of the companies they report in audits as safe," according to one former auditor interviewed by Bloomberg Markets.

One employee at a company that conducts inspections on behalf of the FDA went so far as to say that "If you have a program for adding rat poison to a food, the auditor will ask, 'Did you add as much as you intended?' Most won't ask, 'Why the hell are we adding poison?'"

The situation is even worse when it comes to imported food. There, most food production plants are subject to virtually no inspection. Just 2.7 percent of the food that is imported from abroad is subject to inspection. Much of the rest is theoretically vetted by foreign inspectors -- but many of those inspections are far less rigorous than those in America (take the evidence from the recent massive Canadian beef recall as one example). Bloomberg Markets reporters visited several Mexican farms and found deplorable conditions. That's especially alarming considering that by 2030, half of the food we consume in the U.S. will be imported. Already, about a fifth of the food we eat is currently imported. And for certain foods, that figure is much higher. Here's a chart from the Bloomberg Markets story indicating the most frequently-imported foods:

Some of the issues uncovered in the Bloomberg Markets investigation are addressed in 2011's landmark Food Safety Modernization Act. But many of the provisions of that bill have yet to be implemented. If there were ever a case for fixing that, this article makes it. Be sure to read it in its entirety -- including several compelling personal stories of people affected by contaminating food -- at Bloomberg Markets magazine.