the face of strict appellation and protection rules in the EU, which Croatia joins on July 1, tradition and local pride had to give way, although local winemakers say it's not over yet.

the face of strict appellation and protection rules in the EU, which Croatia joins on July 1, tradition and local pride had to give way, although local winemakers say it's not over yet.The reality check came in March, when the agriculture ministry suddenly announced the traditional sweet dessert wine known as prosek could no longer be sold under its name.

Prosek was considered too similar to Italy's prosecco, which enjoys protected status under the same EU rules which say wine labeled champagne must be made in the Champagne region of France.

Only a few weeks later, Slovenia said Croatia had no right to produce and market teran, a red wine made in the northern tip of the Adriatic, shared by Italy, Slovenia and Croatia.

The news prompted some local winemakers to say "if they want a wine war, they'll get it", while Andro Tomic, a major wine and prosek producer from Jelsa on the southern island of Hvar, said Croatia was largely to blame for its own failure.

"We had had so much time and could have done a lot more but the ministry just did not consult us," Tomic said.

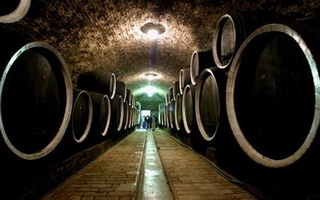

"The way things are going, who knows what else is in store for us," he told Reuters in his wine cellar, a majestic building made of stone blocks where tourists sip and buy his reds, whites, roses and dessert wines.

WHAT'S IN A NAME?

The irony, he says, is that prosek and prosecco are completely different, with the only similarity in the name.

The amber-hued prosek is made from dried grapes, often laid out to dry in straw-covered attics and drunk as a strong dessert wine. Prosecco is a light sparkling wine similar to champagne.

Unless Croatia manages to prove the difference and get the ban lifted, the local producers will have to change its name, something Tomic said was unthinkable.

"Prosek is simply a part of our tradition. It's like saying 'We're going to confiscate a part of your sea', it just won't work," he said.

The association of prosek makers will now engage the agriculture ministry and lawyers specializing in intellectual property and probably take the case to court.

Croatia negotiated EU membership for eight years and concluded the talks in 2011 but has done little to register some of its food products.

With its crescent-shaped fertile plains in the east, a lush, hilly north and the Mediterranean south, Croatia has a varied cuisine with Italian, Austrian, Hungarian and Ottoman Turk influences.

So far it has registered only 12 food products, including olive oil, turkey meat, two varieties of coleslaw and three of smoked ham similar to Italian prosciutto. Only one of the 12, the Istrian Prsut, is in the process of getting the EU-wide registered mark.

REGISTER IN EU, SELL LOCALLY

Deputy agriculture minister Davorka Hajdukovic said many local producers feared long registration procedures or failed to realize the benefits it would bring.

"Today, when the market is flooded with products of suspicious origin and quality, consumers are ready to pay more for something made in the traditional way, with high quality ingredients," she said.

While winemakers are preparing to do battle, producers of the kulen sausage are a step ahead. Kulen is a thick and spicy sausage made of prime pork meat, paprika and garlic stuffed in a pig's appendix and hung out to dry for at least six months.

Kulen producers from Baranja in the northeast of Croatia already registered 'Baranjski Kulen' in Croatia and are preparing to apply for EU registration.

"There is no point in stopping with the local registration, we have to go to the EU. It's proved to be great for marketing, but you can only register a quality product, something your region is proud of," said Goran Kusec, a food technology professor who acted as advisor to the kulen producers.

Most of the kulen is produced at local farmsteads, with only one major meat plant, Belje, able to turn out larger quantities.

"I am sure that bigger producers, like Belje, are thinking about selling kulen in Europe, but as a small producer, I have different ideas," said Sanel Rajkovic from the village of Lug in the northeast Baranja region.

He tends his own pigs and produces about 1,000 kulens a year, selling them at 180 kuna ($30.99) per kg.

"I want my guests to come to my house and taste healthy food made without nitrates, without chemicals, to see where it is produced," he said.