Recently, we have been hearing persistent claims of declining shark fin imports into Hong Kong. But many of the reports - both in local and international media - have been guilty of peddling misinformation, which has created confusion around the real issue.

Claims from the shark fin industry of a drop in imports of some 30 per cent - and even one report of 70 per cent - are exaggerated. Data from the Census and Statistics Department clearly indicates a 19.8 per cent drop in imports from 2011 to 2012. What's more, for the 15 years up to and including 2011, shark fin imports have remained relatively constant at about 10,000 tonnes a year, albeit with some fluctuations.

Claims from the shark fin industry of a drop in imports of some 30 per cent - and even one report of 70 per cent - are exaggerated. Data from the Census and Statistics Department clearly indicates a 19.8 per cent drop in imports from 2011 to 2012. What's more, for the 15 years up to and including 2011, shark fin imports have remained relatively constant at about 10,000 tonnes a year, albeit with some fluctuations.

That contrasts significantly with the figure of 1,162 tonnes recently reported for 2012. The exaggerated drop in the 2012 figure, which was widely reported, is probably a result of the fact that the codes under which shark fin products are reported were revised in the 2012 government data.

A large quantity of fins were recorded against a previously rarely used code and omitted from the total figure reported.

The decline also started well before major airlines, led by Cathay Pacific last December, took the bold and much welcome step of banning the carriage of shark fin. About 15 per cent of all shark fin is imported into Hong Kong by air; the majority still comes by sea.

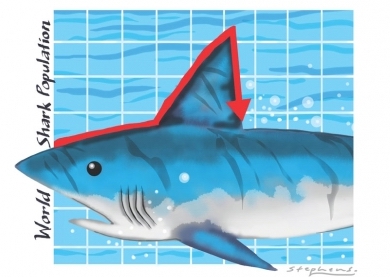

Yet, despite the 2012 decline, Hong Kong has retained its leading and historic position representing about 50 per cent of the global total, indicating that the drop is likely to be global in nature. The good news could be that demand and consumption are falling - which has also been widely reported. The bad news could be that there are simply fewer sharks in the oceans, a very real possibility according to scientists. Or, it could be a combination of both.

Whichever way, until we see a significant downward trend that can be attributed to reduced consumption, there is much reason for concern. Overfishing is driving many shark species towards extinction and by the time we see such a trend emerge, it will probably be too late to do anything about it.

Given the importance of sharks to the marine ecosystem, it is surely imperative that we follow the precautionary principle - that an activity shouldn't be continued if the consequences are potentially damaging - and seek to regulate the trade.

Another issue frequently reported is the impact it has on fishermen, including claims that non-governmental organisations are responsible for reducing demand and thus depriving poor communities of their livelihoods. While the rationality of this argument is without question, we should look more closely at the real situation and those who raise it.

In reality, it is the traders who profit from shark fin, not the fishermen. About 10 years ago, fishermen along the southeastern coast of Mozambique switched to catching sharks - purely to sell the fins to Asian traders - as the meat had little monetary value and was eaten by local villagers.

But, by 2011, the fisherman had to switch back to catching reef fish as shark populations had dwindled due to over-fishing, also depriving the locals of a previously constant source of protein. These fishermen would have gained far more in terms of food security and future livelihoods from the sustainable management of shark fisheries.

In contrast, in Hong Kong's infamous shark fin district, it's not uncommon to see Bentleys, Ferraris and the occasional Rolls-Royce parked beside shark fin wholesalers. Surely that's not a coincidence?

Finally, are many shark species at risk of extinction? The answer - if observing the internationally recognised International Union for Conservation of Nature's Red List - is a resounding "yes". Of the 262 shark species where there is sufficient data to assess their conservation status, 54 per cent, or 142 species, are at risk of extinction either now or in the near future.

Confusion arises as the trade in Hong Kong is regulated through The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, under which only eight species are on the list, five of which were only added this March following years of contesting claims. It's hardly surprising there are so few on this list when you consider the lobbying that goes on as countries seek to avoid regulation of the trade in a lucrative, albeit endangered, species.

While NGOs have been relentless, with good reason, we should not forget that last year 41 of the world's leading marine scientists wrote to the Hong Kong government expressing concern over the impact of the fin trade on global shark populations.

The government seems to have done its research and, last Friday, it issued an internal circular recommending that shark fin should not be served at official functions and, furthermore, when functions are organised by others, the relevant bureaus and departments should notify their hosts in advance that government officials will not be eating shark fin. This is also a way to use a unique opportunity to educate others.

Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying and his administration should be applauded for taking what is hopefully a first step in addressing Hong Kong's role in the decimation of shark populations worldwide.

A large quantity of fins were recorded against a previously rarely used code and omitted from the total figure reported.

The decline also started well before major airlines, led by Cathay Pacific last December, took the bold and much welcome step of banning the carriage of shark fin. About 15 per cent of all shark fin is imported into Hong Kong by air; the majority still comes by sea.

Yet, despite the 2012 decline, Hong Kong has retained its leading and historic position representing about 50 per cent of the global total, indicating that the drop is likely to be global in nature. The good news could be that demand and consumption are falling - which has also been widely reported. The bad news could be that there are simply fewer sharks in the oceans, a very real possibility according to scientists. Or, it could be a combination of both.

Whichever way, until we see a significant downward trend that can be attributed to reduced consumption, there is much reason for concern. Overfishing is driving many shark species towards extinction and by the time we see such a trend emerge, it will probably be too late to do anything about it.

Given the importance of sharks to the marine ecosystem, it is surely imperative that we follow the precautionary principle - that an activity shouldn't be continued if the consequences are potentially damaging - and seek to regulate the trade.

Another issue frequently reported is the impact it has on fishermen, including claims that non-governmental organisations are responsible for reducing demand and thus depriving poor communities of their livelihoods. While the rationality of this argument is without question, we should look more closely at the real situation and those who raise it.

In reality, it is the traders who profit from shark fin, not the fishermen. About 10 years ago, fishermen along the southeastern coast of Mozambique switched to catching sharks - purely to sell the fins to Asian traders - as the meat had little monetary value and was eaten by local villagers.

But, by 2011, the fisherman had to switch back to catching reef fish as shark populations had dwindled due to over-fishing, also depriving the locals of a previously constant source of protein. These fishermen would have gained far more in terms of food security and future livelihoods from the sustainable management of shark fisheries.

In contrast, in Hong Kong's infamous shark fin district, it's not uncommon to see Bentleys, Ferraris and the occasional Rolls-Royce parked beside shark fin wholesalers. Surely that's not a coincidence?

Finally, are many shark species at risk of extinction? The answer - if observing the internationally recognised International Union for Conservation of Nature's Red List - is a resounding "yes". Of the 262 shark species where there is sufficient data to assess their conservation status, 54 per cent, or 142 species, are at risk of extinction either now or in the near future.

Confusion arises as the trade in Hong Kong is regulated through The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, under which only eight species are on the list, five of which were only added this March following years of contesting claims. It's hardly surprising there are so few on this list when you consider the lobbying that goes on as countries seek to avoid regulation of the trade in a lucrative, albeit endangered, species.

While NGOs have been relentless, with good reason, we should not forget that last year 41 of the world's leading marine scientists wrote to the Hong Kong government expressing concern over the impact of the fin trade on global shark populations.

The government seems to have done its research and, last Friday, it issued an internal circular recommending that shark fin should not be served at official functions and, furthermore, when functions are organised by others, the relevant bureaus and departments should notify their hosts in advance that government officials will not be eating shark fin. This is also a way to use a unique opportunity to educate others.

Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying and his administration should be applauded for taking what is hopefully a first step in addressing Hong Kong's role in the decimation of shark populations worldwide.