The Ritz-Carlton hotel in Osaka and the Renaissance Sapporo Hotel in Hokkaido, for example, recently admitted using ingredients that are cheaper or more easily obtained than the premium items advertised on their menus.

On Thursday, even the prestigious Imperial Hotel Ltd. admitted that it once served frozen juice labeled as “fresh” at restaurants in its Tokyo and Osaka hotels.

Imperial said the orange and grapefruit juices had been served until May 2006 and May 2007, respectively, after procuring freshly squeezed juice from a Tokyo supplier in frozen form. The juices are now being served freshly squeezed.

High-end eateries, such as those in luxury hotels, often tout the quality and safety of their fare to provide an air of exclusivity while cutting costs in the kitchen.

The government “is stepping up” regulations on food labeling, including product origin explanations for items sold in shops, but interestingly enough, the government’s regulations do not apply to restaurant menus.

While the Consumers Affairs Agency studies whether Japan’s latest food fraud cases fall under the scope of a more general law — the competition policy law to prevent all types of businesses from mislabeling products — the credibility of restaurant menus will be left in the hands of the businesses.

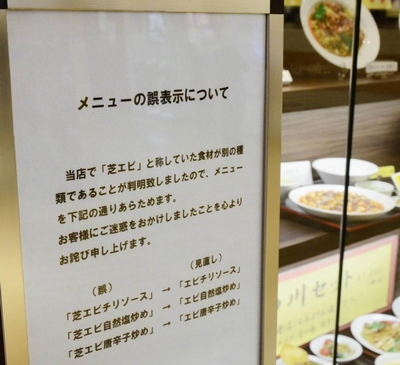

“We called big ones Japanese tiger prawns and small ones ‘shiba’ shrimp. It was an established display practice at the restaurant,” Renaissance Sapporo General Manager Hiroshi Harata admitted at a news conference Tuesday to apologize for the misrepresentations that took place in its restaurants.

The Hokkaido hotel was using cheap shrimp at its Chinese restaurant that differed from the shrimp listed on the menu. His explanation echoed the one issued by Hankyu Hanshin Hotels.

False advertising has also surfaced at three restaurants owned by a Shikoku Railway Co. subsidiary in Tokushima and Ehime prefectures, and hotels in Hamamatsu, Shizuoka Prefecture, and in Otsu, Shiga Prefecture.

The labeling of foods that can easily be confused with upscale products are regulated by the Agricultural Standards Law.

Fish merchants, for example, used to be able to label Patagonian toothfish as “ginmutsu,” a name reminiscent of the pricey “mutsu” fish. Now it is required to be called “mazeran ainame” (Magellan greenling) or “mero.”

Restaurants, however, are above the law. They are also above a new food labeling law due to take effect as early as spring 2015 that will combine three existing food laws, including the Agricultural Standards Law.

The logic of leaving restaurants unregulated is simple — according to the government.

“It is because it can be assumed that (the origin of) food served at restaurants can be explained if you ask about it on the spot,” an unnamed civil servant in charge of the matter at the Consumer Affairs Agency said.

The origins and producers of food are increasingly being identified at restaurants, including those in hotels, amid rising concerns about food safety, especially in light of the Fukushima meltdown disaster.

Michiko Kamiyama, a lawyer representing the group Food Safety Citizens’ Watch, said many customers have high expectations for food served by restaurants linked to expensive hotels.

“Customers make efforts to dine at hotels because they seek added value. They are expecting to get something that is worth the money they are spending.”

Gurunavi Inc., which runs an online restaurant guide, conducted a poll in 2009 to find out what kind of menu information puts guests at ease.

According to the poll, 72.5 percent want to see the “product origin,” followed by “calorie content,” “ingredient and nutritional information” and “taste and texture.”

The fifth most sought-after piece of information was “food producers,” with 26.3 percent, the poll of about 1,500 people said.

Gurunavi told restaurant managers who are members of the site that efforts to convey they are using carefully selected products will be an asset to their businesses and help generate fare that attracts customers.

“It has become difficult for consumers to discern (ingredients) by taste. They can only believe in professionals serving food. The psychological damage stemming from the betrayal (caused by the frauds) is considerable,” said Tomoko Yoshida of Gurunavi’s public relations group.

After serving up to 47 types of ingredients different from those advertised on its menus for seven years, Hankyu Hanshin Hotels has refunded at least ¥20 million to more than 10,000 customers so far.

Among other misrepresentations, its restaurants lied about the areas where its vegetables were grown and claimed the ready-made cakes and chocolate sauce it was serving up were handmade.

Like other firms, the hotel chain’s main business took a hit from the 2008 global financial crisis. So it started lying about the food on its menus in a bid to bring in patrons, according to Hankyu Hanshin Hotels President Hiroshi Desaki, who said Monday he would step down to take responsibility for the scandal.

In the restaurant industry, it is widely believed the main tenet of profitability is reducing food and labor costs. The eateries in the scandals were likely trying to slash food costs to “maintain quality of service.”

“Menu descriptions were created to meet consumers’ preference for brand products, and when they couldn’t obtain the stated ingredients, they just used food from different places of origin and may have become inured to the practice before it became a custom,” claimed hotel and eatery consultant Hiroshi Tomozawa.

Based on his 40 or so years in the hospitality industry, Tomozawa said there is a need to improve communication within the organization and to allow a different section to check all the products sourced by the purchasing unit.