The animal reported to be a five year old Red and White Roodbont cow, part of a herd of 120, was not presented for slaughter and did not enter the food chain.

The Irish agriculture department said that tests to confirm the case were taking place and the results are expected this week.

The agriculture department is carrying out a full investigation into the case including an examination of the birth cohort and progeny of the cow involved and it said that it has informed the relevant international authorities, the European Commission and Ireland’s trading partners.

The full range measures to control the risk continue in place at slaughter plants, including:

All animals presented for slaughter are systematically subjected to ante-mortem examination by veterinary inspectors to ensure that only healthy animals are allowed into the food chain.

A range of tissues - identified as ‘specified risk material’ - where the BSE infectivity resides in potentially infected animals are systematically removed from all slaughtered cattle of differing ages as follows:

All ages: tonsils, intestines and mesentery

Over 12 months: skull (including eyes and brain) and spinal cord

Over 30 months: the vertebral column and associated tissues

There are concerns in Ireland that this latest case could damage newly forged trading partnerships.

Ireland has just reopened its beef trade with the USA and is in ongoing negotiations with the Chinese over a potential new trade deal.

When Ireland’s risk status was changed from controlled to negligible at the beginning of June, the Irish agriculture minister Simon Coveney said: ““BSE had caused very considerable disruption to trade in the beef sector in the past and the measures taken both to protect public health and to eradicate the disease had imposed very considerable costs on the beef sector.”

He added: “The OIE decision will further advance Ireland’s reputation with other beef markets around the world.”

Following the announcement of the suspected case being discovered, the Irish food marketing body Bord Bia said: “The identification of a suspected BSE case in Co. Louth today is clear evidence that Ireland’s rigorous animal health and food safety controls continue to operate effectively.

“This isolated case is unfortunate, coming after the recent decision of the OIE to award Ireland ‘negligible risk status’.

“However, Ireland retains its ‘controlled risk status’ under which it has, and continues to, trade successfully in Europe and internationally.

“It is this ‘control risk status’ that has also enabled Ireland to achieve access to the US, Japan and to secure the recent lifting of the beef ban in China.

The spokesman added: “Bord Bia is confident that this isolated case will not adversely impact on the reputation of Irish beef among its European and international customer base.”

“We will nevertheless continue to monitor any reaction overseas and remain in close contact with both exporters and customers through our international office network.”

BSE in Ireland

BSE was first confirmed in cattle in the UK in 1986. The first case in Ireland was confirmed in 1989, when there were 15 cases confirmed.

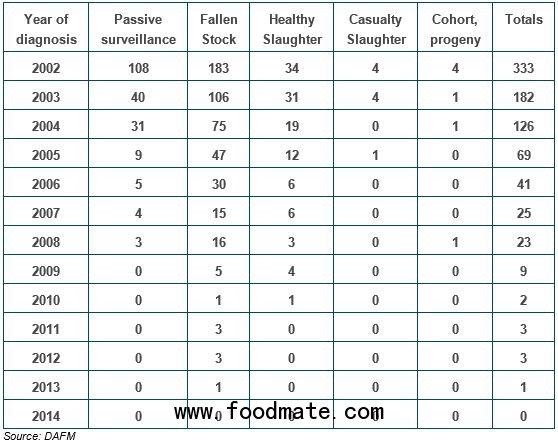

If the present case in Louth is confirmed, as is considered likely, it will bring the total number of cases in Ireland to 1656 since 1989.

The height of the outbreak was between 2000 and 2004, reaching its peak in 2002 when 333 cases were reported.

However, following the introduction of strict surveillance and monitoring systems the number of cases fell and more and more cases were being detected through the active and then passive surveillance systems rather than through the discovery of clinical cases.

Under the passive surveillance programme, veterinary surgeons and farmers are alerted to the symptoms of the disease and report all suspect animals.

When a report of an on-farm suspect animal is received, the animal is examined by a veterinary inspector from a Regional Veterinary Office.

In abattoirs, animals are examined ante-mortem for signs of diseases, including BSE and any animal deemed to be an official BSE suspect is destroyed, and the herd in question is immediately placed under official restriction and quarantined.

Under the active surveillance programme, brain samples are taken from the carcases of all cattle more than 48 months old that die on farm.

Those below that age have been shown to have an extremely low incidence of BSE.

If an animal is detected as positive on the screening test, a full investigation similar to that carried out in passive surveillance, takes place.

Active surveillance in slaughter plants consists of samples being taken from all casualty and emergency slaughter animals over 48 months of age.

Irish Farmers’ Association President Eddie Downey said: “This isolated case shows the effectiveness of the monitoring and control systems in place in Ireland.”

He said the traceability and monitoring controls adopted by farmers and the sector are the most stringent and robust anywhere and ensure the health status and quality of Ireland’s agri-produce. “

A random case is not unusual in the context of the robust control systems we have in place for all diseases,” Mr Downey added.

Most experts believe that BSE was most likely spread by cattle eating feed that contained contaminated Meat and Bone Meal (MBM), which is produced through rendering.

In 1990 a ban on the feeding of MBM to ruminant animals was introduced.

In 1996 and 1997 the BSE control measures in place in Ireland were reinforced following the identification of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in humans.